A 50-vessel parade marks the 50th anniversary of the Cyprus Peace Operation.

© picture alliance / Anadolu | Emin Sansar

A 50-vessel parade marks the 50th anniversary of the Cyprus Peace Operation.

© picture alliance / Anadolu | Emin Sansar

Special thanks to Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, Arthur Buliz, Michael Westrich and Ben Zimmermann

December 10, 2025

This visual platform provides an overview of Turkey’s evolving foreign policy activism. It combines maps, charts, and short explanatory texts to illustrate Turkey’s capabilities, tools, and areas of engagement and to show how the various instruments are deployed by the country’s decision-makers. The aim is to offer an accessible, structured summary of Turkey’s increasingly multidimensional foreign policy. This visualisation is an update of the one first published in 2020 and subsequently updated in 2021. It reflects the regional and global shifts that have taken place over the past four years.

Since the previous update, ground-breaking developments in global politics – including the war in Ukraine and the 7 October 2023 attacks against Israel, followed by the armed conflict with Hamas that extended beyond Gaza – have reshaped regional dynamics in the Middle East, the Black Sea, and the Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey’s role as a regional actor has gained further weight, while the overarching direction of its foreign policy activism, evident from the earlier visualisation, shows a continuity in the use of military activism and security cooperation combined with diplomatic mediation efforts, economic and development cooperation, and participation in multilateral institutions.

Turkish foreign policy has attracted a great deal of attention ever since the country began flexing its muscles in its immediate neighbourhood. For this reason, the project starts with a visualisation that plots Turkey’s active military operations, military bases, training missions, and peacekeeping deployments beyond its borders. This is followed by detailed maps and brief explanations of Turkish military engagements in Syria, Libya, and Iraq as well as a section that addresses Turkey’s role in Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean. All the visuals highlight how military instruments have become a prominent feature of Turkey’s regional strategy.

Turkey’s military presence is growing at a time when its defence industry is rapidly expanding. Three consecutive charts outlining the long-term trends in Turkey’s defence expenditure and shifting import-export ratio illustrate how domestically produced systems have become central components of Turkish power projection. There is also background information on the development and strategic significance of the sector.

But hard-power tools are just one dimension of Turkey’s foreign policy activism. This visual platform also explains Turkey’s engagement with multilateral organisations, its diplomatic outreach, and its economic and development assistance programmes. These elements are mapped chronologically to show how Turkey has sought to reinforce its regional and international standing through a combination of political, economic, and security instruments.

All data and all information included in the maps as well as in the text are current as of November 2025.

The Turkish leadership continues to frame the country’s external posture around the idea of its becoming a significant regional power within what is an increasingly multipolar international environment. Beyond economic instruments and diplomatic outreach, Ankara has relied heavily on military tools to sustain this ambition. The steady expansion of Turkey’s overseas military footprint – particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa – forms part of this broader strategy. Over the past decade, Ankara has established and consolidated several bases and training missions in its immediate neighbourhood and farther afield in order to project presence, provide security assistance, and shape regional dynamics.

At the same time, Turkey has remained militarily active in contested theatres within its near abroad. In Syria, Turkey has become one of the new regime’s main external backers, with its military deployments shaping the Syrian evolving power configuration. In Libya, Turkish involvement – which includes advisory missions, the supply of drones, and the deployment of allied non-state actors – has directly influenced the balance of power, even as the intensity of the conflict has waned. And in Iraq, successive cross-border operations over the past decade have resulted in a lasting military presence that now appears structurally embedded as part of sustained operations and series of military bases established in northern Iraq. These developments point to a long-term trend in which military instruments remain central to Turkish foreign and security policy. Discussions in Ankara about establishing more naval facilities and continuing to promote Turkey’s rapidly expanding defence industry suggest this trajectory will persist in the coming years.

Often described as the second-largest army in NATO, the Turkish military has a long history of cross-border engagements. Before the Arab uprisings, Turkey’s overseas military activities – except those in Cyprus and parts of northern Iraq – took place largely within NATO and UN frameworks. Over the past decade, however, there has been a marked shift towards a unilateral approach. Turkey has carried out sustained operations in neighbouring conflict zones, while at the same time establishing forward bases and undertaking long-term deployments. As a result of these developments, Syria, Libya, and Iraq have become the main theatres of direct Turkish military involvement. The sections below provide maps and brief explanations of the military dynamics in these three arenas as of 2025.

Turkey’s role in Syria has changed profoundly over the course of the conflict. Initially, Ankara pursued the clear political objective of removing President Bashar al-Assad and supported a wide range of opposition groups, including the Free Syrian Army (FSA). When regime change ceased to be a priority, Turkey increasingly focused on preventing the emergence of an autonomous Kurdish political entity along its southern border and curbing further refugee inflows. In line with these objectives, it launched four cross-border operations between 2016 and 2020, establishing Turkish-controlled areas in northern Syria, shown on the map above as territories held by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA). Formed through the merger of disparate opposition factions, the SNA operates under substantial Turkish direction and functions as Ankara’s main proxy force west of the Euphrates and in the corridor between Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ayn.

Under Assad, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which originally emerged from jihadist networks in Syria, had long been the dominant force in Idlib, a position made possible by Turkey’s military posture and political protection in the northwest. When the Assad regime eventually collapsed – as a result of internal decay and the inability of its key external backers (notably Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia, which had grown weak owing to the war in Ukraine) to continue providing support – HTS capitalised on the power vacuum that ensued. Building on the administrative and military structures it had developed in Idlib, the group expanded its reach southward and, on 8 December 2024, took control of Damascus. However, it does not have full control over a vast but sparsely populated region to the east (marked as “lost regime territory” on the map above) and thus has been unable to fully consolidate its post-regime change territorial reach. HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharra now serves as Syria’s interim president. Although the new authorities have achieved a degree of internal and external recognition, the country remains significantly weakened after more than a decade of civil war, while governance is characterised by institutional fragility and the enormous challenge of rebuilding a state that had failed to deliver most basic services.

Turkey has emerged as the most important external supporter of the new Syrian authorities. While HTS is not a direct Turkish proxy, the group’s rise and consolidation of power have been possible owing to Ankara’s long-standing protection and military deterrence in the northwest of Syria. Over time, Turkey and HTS have come to see eye to eye about the idea of reconstructing a more centralised governance structure in Syria. Ankara has provided diplomatic backing to the new leadership, which may expand into more formal military support. The SNA has publicly declared its intention to integrate into the national armed forces announced by the new Syrian authorities, although no such process has yet begun and the new army remains in its early formative stage. Turkey has explored contributing to the formation and training of the new Syrian military and establishing bases inside the country, but those plans have not yet materialised either and face strong resistance from Israel.

Meanwhile, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led multi-ethnic coalition, continue to control most of northeast Syria. Earlier, under Assad, the SDF had established the institutions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), which it continues to govern today. Following the regime’s collapse, it withdrew completely to the east of the Euphrates and from time to time has engaged in negotiations about possible political and military integration with the new authorities in Damascus. The US maintains a limited military presence in the northeast and continues to support the SDF as its principal on-the-ground partner in operations against ISIS remnants. It also has a military foothold at the Al Tanf garrison near the border triangle between Iraq, Jordan, and Syria, which functions as a deconfliction zone and a base for counter-ISIS operations. The new Syrian authorities formally joined the US-led international coalition against ISIS on 10 November 2025.

For its part, Israel has significantly expanded its military footprint in southern Syria. Beyond its longstanding occupation of the Golan Heights, it has further extended its control and military presence in the south since 8 December 2024, which it describes as a security measure. Now, whenever it deems such action necessary, it delivers strikes not only against armed groups it views as hostile but also against the emerging military infrastructure and capabilities of the new Syrian authorities. Israeli-controlled zones and buffer areas, as shown on the map above, add another layer to Syria’s fragmented territorial order.

Sources: ISWN Middle East Conflict Map, EIA

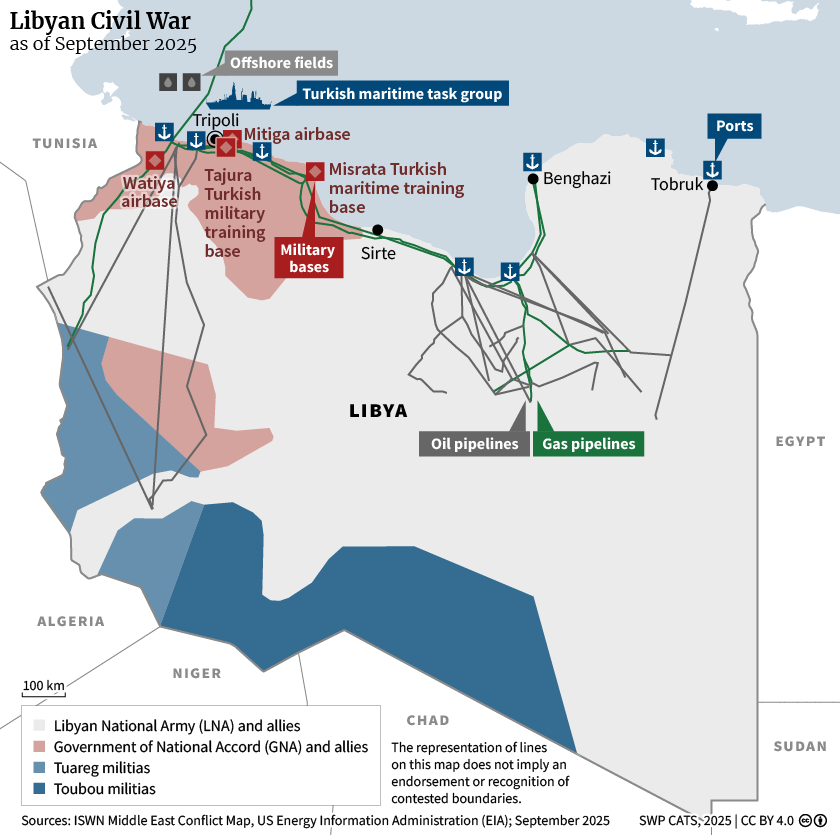

Turkey was a latecomer to the Libyan conflict. Its direct military involvement began in 2019, when Ankara intervened to support the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli against General Khalifa Haftar’s offensive. In line with the relevant UN Security Council resolutions, Turkey viewed the GNA under Fayez al-Serraj as Libya’s legitimate authority, while Haftar received backing from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, France, and Russia. Ankara’s decision to intervene was closely tied to its broader strategic calculus in the Eastern Mediterranean: its cooperation with the Tripoli government enabled the conclusion of the contested maritime delimitation agreement in November 2019.

Since 2019, Turkey has deployed drones, armoured vehicles, military advisers, and intelligence personnel to Libya and has established several training centres to promote the restructuring of the Libyan security forces. While, initially, Turkey combined its advisory role with the deployment of armed drones and supported the effort by enabling the transfer of Syrian fighters aligned with Tripoli-based forces, it significantly expanded its operational presence in subsequent years. Various international reports indicate that Ankara now maintains a military presence of several thousand Turkish and Syrian personnel in western Libya, reflecting a shift from a limited advisory role to a more substantial and structured deployment. Despite the UN arms embargo, there have been continued violations by many external actors; and Turkey justifies its military assistance on the basis of invitations from the internationally recognised authorities in Tripoli. In addition, Turkish naval elements – in the form of a Turkish maritime task group – continue to operate off the Libyan coast in support and coordination roles.

Following the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in early 2021, which, in practice, governs only western Libya, Ankara’s military presence remained largely intact as the two sides reaffirmed earlier agreements. Over time, Turkey has also developed pragmatic contacts with actors in eastern Libya – namely, General Haftar – reflecting a broader effort to safeguard its political, military, and economic footprint amid the country’s fragmented institutional landscape.

Since the 1990s, the Turkish military has carried out dozens of cross-border operations against bases of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) inside Iraq and maintained permanent military facilities in the north of the country. These bases, most of which are to be found along the Turkish-Iraqi border, were established under security agreements concluded with Baghdad and local Kurdish authorities in the mid‑1990s. Later, they continued to operate through a tacit understanding with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Unlike in Syria, Turkey does not control any territory in Iraq. However, by establishing a series of military bases along the Turkish-Iraqi border, it has created a de facto security zone. Although it is not militarily feasible to target the main PKK camps in and around the Qandil Mountains from these bases owing to the harsh terrain (moreover, the Qandil Mountains are located farther south and a long way from the Turkish-Iraqi border), the dozen or so Turkish military bases form a buffer between the PKK forces and Turkish territory.

In October 2024, Ankara launched a new peace initiative under which the PKK announced a unilateral cease-fire and declared its intention to disarm and disband. While the outcome of this process remains uncertain and there are significant doubts about whether it will continue, cross-border Turkish military operations in northern Iraq appear to have ceased for the time being. Turkey’s network of military bases in the region remains in place, however.

Another important Turkish military installation is located in Bashiqa, near Mosul, close to the line separating the KRG from federal Iraqi territory. Originally established in 2015 to train Kurdish Peshmerga and Sunni Arab fighters against ISIS, the base became a bone of contention between Turkey and Iraq, as Baghdad repeatedly demanded its closure, arguing that it lacked federal authorisation. Ankara countered that the base had been built at the request of the then governor of Mosul and within the framework of its security coordination with the KRG. In recent years, the dispute began to diminish in intensity; and in 2024, Turkey and Iraq agreed to transform the Bashiqa facility into a Joint Training and Cooperation Centre under Iraqi command and establish a Joint Security Coordination Centre in Baghdad. This shift reflects Ankara’s effort to frame its military presence as part of a co-managed security arrangement rather than a unilateral prerogative.

In 1959, as British rule in Cyprus was nearing its end, the United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey agreed to establish the bi-communal Republic of Cyprus and designated themselves as the guarantor powers. Following the 1974 coup by Greek and Greek Cypriot forces aiming to forge a union with Greece, Turkey intervened under the Treaty of Guarantee and later expanded its control to roughly 38 per cent of the island. Since then, Cyprus has been divided into two parts: the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus in the south and the Turkish Cypriot administration in the north, which is supported by Turkish military forces.

Regarding reunification efforts, the 2004 Annan Plan, which, drawn up by the UN, aimed to allow a united and independent Cyprus become an EU member state, remains the most comprehensive attempt to date at finding a solution to the Cyprus problem. But because the Greek Cypriots rejected the plan in a referendum – whereas the Turkish Cypriots voted to accept it – a settlement could not be reached. In the same year, the Greek Cypriots joined the EU while the Turkish Cypriots remained in their non-recognised breakaway state in the north. Intensive peace talks on Cyprus between 2014 and 2017, failed to overcome the impasse, with the final round held at the UN-facilitated Crans-Montana summit in 2017.

In 2020, the Turkish Cypriot authorities, backed by Ankara, partly reopened Varosha, a long-sealed coastal district of Famagusta under military restrictions since 1974, and Turkey’s approach increasingly shifted towards a two-state solution. The same year, it threw its support behind the pro-Turkey candidate, Ersin Tatar, in the presidential election in the breakaway state. Despite continued strong backing from Turkey, Tatar lost the 2025 presidential election to Tufan Erhürman, who favours renewed efforts towards establishing a united Cyprus. While this outcome has led to greater uncertainty, it has not altered Turkey’s continued strategic focus on the island.

Over the past decade, the Eastern Mediterranean has been a central arena of geopolitical tensions owing to unresolved maritime boundary disputes, competing claims over exclusive economic zones (EEZs), energy-resource discoveries, and periodic naval brinkmanship. Turkey’s strategic posture in the region reflects both long-standing disputes with Greece and the Republic of Cyprus and the broader recalibration of its foreign policy since 2020. While the period 2018–20 was marked by assertive moves, including the deployment of seismic survey and offshore drilling vessels into contested maritime zones, the signing of maritime boundary memoranda with Libya, and the use of naval escorts to accompany energy missions, Ankara has since gradually adopted a less confrontational mode of engagement.

Turkey contests the maritime boundaries claimed by Greece and the Republic of Cyprus, arguing that islands – particularly small and remote ones such as Kastellorizo – should not enjoy full EEZ or continental shelf rights. Turkey’s own claimed continental shelf partly overlaps with the EEZs that Cyprus has delineated in agreements with Egypt and Israel.

Two key agreements have shaped Ankara’s legal and political framing:

In summer 2020, tensions escalated sharply when Turkey deployed seismic research vessels and naval escorts to areas that Greece considers part of its EEZ, triggering a crisis and heightened rhetoric that lasted for several weeks. Turkey ceased such deployments in late 2020, partly in response to EU pressure and the prospect of expanded sanctions. The de-escalation coincided with Ankara’s broader decision to stabilise relations with key regional actors and reduce its diplomatic isolation. Exploratory talks resumed in early 2021 but there has been no substantive progress made to date.

Many of Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean have been based on the “Blue Homeland” (Mavi Vatan) doctrine, which promotes expansive maritime jurisdiction claims and a forward defence posture extending from the Black Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean. The doctrine was especially influential during the peak tensions in 2019–20.

Since then, the influence of hardline “Blue Homeland” advocates within Turkish foreign policy circles has diminished and Ankara has adopted a less confrontational stance. The doctrine itself, however, remains a policy template that Ankara could reactivate at any time if it were to return to a more confrontational regional strategy. The shelving of the economically and politically fraught EastMed gas pipeline project helped further reduce regional frictions. At the same time, Turkey sought to counter its isolation in the Eastern Mediterranean. The growing cooperation between Greece and Cyprus, on the one hand, and Egypt, Israel, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, on the other, was perceived by Ankara as an emerging anti-Turkey alignment that would weaken its position in the region. Thus, Turkey’s efforts to improve relations with the last-named four countries have also served the purpose of reducing its regional isolation, although ties with Israel have deteriorated once again following the 7 October attacks.

Turkey assigned significant importance to mediation in the mid-2000s, particularly under Ahmet Davutoğlu’s stewardship, when Ankara sought to position itself as a proactive diplomatic force capable of engaging multiple regional actors. In the 2010s, that agenda lost prominence with the Arab uprisings and the shift towards a more confrontational and militarised foreign policy. But in recent years, mediation has regained relevance as Turkey recalibrates its external posture, responds to new regional dynamics, and seeks to leverage its unique position between rival blocs.

Against this backdrop, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 created a new context in which Turkey has attempted to revive its role as mediator. The war significantly narrowed the room for Ankara’s traditional balancing act, which had allowed it to maintain deep political, economic, and security-related ties with Moscow while still being a member of NATO. Nevertheless, Turkey sought to continue that act by supporting Ukraine without openly confronting Russia: it provided military assistance to Kyiv, including drones, but refrained from joining Western sanctions against Moscow. Turkey presented this dual approach as a form of constructive engagement – one that enabled it to serve as an intermediary not only between Ukraine and Russia but also between Russia and the West. The Black Sea Grain Initiative, which, brokered in Istanbul in 2022, was the most visible outcome of such efforts, allowed the Turkish leadership to frame its balancing policy as a prerequisite for sustaining dialogue between the warring parties. Although these initiatives could not alter the overall course of the conflict, they elevated mediation as a revived instrument of Turkish foreign policy.

A similar dynamic unfolded after Israel’s war on Gaza. Turkey attempted to assume a mediating role, but Israel, along with several Arab governments, viewed Ankara as insufficiently neutral and questioned the Erdoğan administration’s credibility as a reliable interlocutor. As a result, Turkey had only limited access to the negotiation tracks led primarily by Egypt and Qatar, which emerged as the principal mediators. Ankara responded by shifting from mediation to leverage in order to remain a relevant diplomatic force in the Gaza war: by openly rejecting the designation of Hamas as a terrorist organisation and adopting an explicitly pro-Hamas stance, it positioned itself squarely as an actor with influence over one of the conflict parties. Towards the end of 2025, this strategy began to pay off and enabled Turkey to re-enter diplomatic discussions from a different angle. This paved the way for its involvement in the ceasefire initiative advanced under the Trump administration’s Gaza plan and Hamas’s eventual acceptance of the proposal. Beyond the Middle East, Turkey has expressed interest in facilitating dialogue in other regional disputes, most notably between Somalia and Ethiopia and between Pakistan and Afghanistan, although these initiatives remain limited in scope and, in the case of the latter, at an early and still fragile stage. To sum up, it is clear that mediation has re-emerged as a visible component of Turkey’s broader foreign policy activism.

Without the cumulative growth of the Turkish defence industry over the past four decades, the pronounced shift to a hard-power approach would not have been possible. If the US arms embargo following Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974 was the first moment when Ankara realised the importance of having a defence industry to protect its national interests, it was the end of the Cold War that underscored the necessity of an independent defence sector.

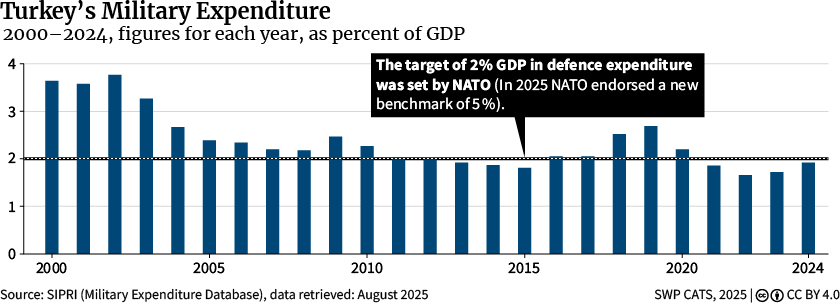

Against the background of these earlier developments, the Turkish defence industry continued to grow rapidly under the rule of the Justice and Development Party (AKP). Between 2010 and 2019 – a period that overlapped with the seeming “soft power” era of Turkey – Turkish military expenditures increased steadily by 86 per cent (see figure: Turkey's Military Expenditure 2000-2024, in US dollars). Aviation and defence exports grew significantly, too, during the same period. According to official figures, around 80 per cent of the aviation and defence inventory of the Turkish Armed Forces is now produced domestically. It is evident that these impressive achievements are a source of pride for the government. At public events, politicians often praise the drones that have been produced domestically by Baykar Savunma – a firm owned by the family of President Erdoğan’s son-in-law, Selçuk Bayraktar – and the state-owned Turkish Aerospace Industries. The latter was established in 1984 as a joint venture between Turkish and US partners and restructured in 2005, when the Turkish partners acquired the shares of foreign investors. The rapid expansion of the sector has also created a sizable defence-industrial ecosystem, generating more than $20 billion in annual turnover and placing several Turkish firms among the world’s top defence producers. This ecosystem has become increasingly intertwined with the political leadership, boosting the government’s ability to leverage defence production both as a tool of domestic legitimation and as a source of external influence.

Turkish drones have attracted significant international attention in recent years. While this was due initially to their deployment in Syria and Libya, their widespread use and effectiveness in Ukraine have elevated them to global prominence. In addition to its drone programmes, Turkey is investing in more advanced platforms – most notably, the fifth-generation KAAN fighter, which, developed by Turkish Aerospace Industries, is expected to enter series production by the end of 2028.

The navy continues to receive substantial investment. Turkey has expanded its MİLGEM programme, under which several new corvettes and frigates have been put into service. In 2023, the entry into service of the TCG Anadolu, an amphibious assault ship capable of operating unmanned aerial systems, was an important milestone in Ankara’s efforts to enhance its maritime power projection. More surface vessels, submarines, and support ships are scheduled for delivery in the coming years. Most of them are being built by Turkish private shipyards or state-owned contractors.

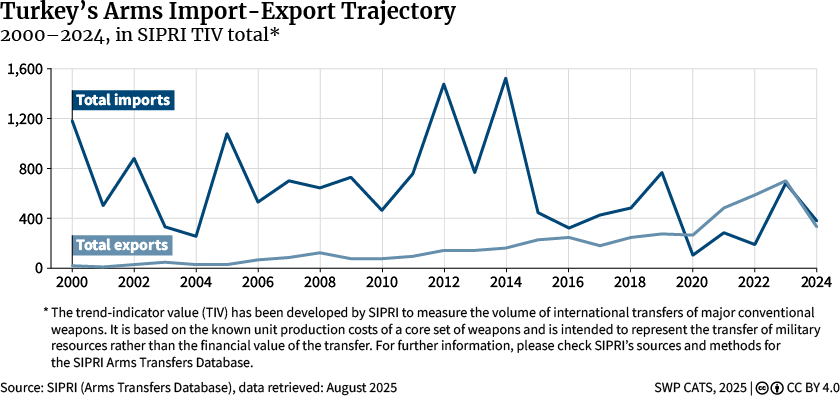

This expansion is strengthening Turkey’s ability to conduct military operations across multiple theatres and reinforcing perceptions in Ankara that the country can act more autonomously in its neighbourhood. At the same time, the rapid growth of the defence sector has become a foreign policy instrument in its own right. Turkey is increasingly using defence-industrial cooperation, arms exports, and joint production agreements to deepen bilateral relationships, particularly with the Gulf states, Central Asian governments, various African partners, and, more recently, Ukraine. These dynamics suggest that the defence industry will remain a key enabler of Turkish foreign policy activism in the years ahead.

The three figures below show how Turkey’s military expenditures and defence industry have developed in recent years.

Turkey's Military Expenditure 2000-2024

Source: SIPRI (Arms Transfers Database)

The sharp decline in Turkey’s arms imports in 2020 was due partly to the increase in domestic production and partly to the impact of official and informal arms embargoes imposed by the US and several European countries. While imports recovered somewhat after 2020, the embargo remained an important factor: it helped accelerate domestic production in the short term but at the same time limited access to key components needed for high-end weapons systems. A prominent example is the KAAN fighter programme. While Turkey’s removal from the F-35 consortium accelerated investment in the development of KAAN, it has experienced ongoing difficulties in securing a suitable engine for the fighter jet, illustrating how embargo-related constraints can slow progress in advanced platforms.

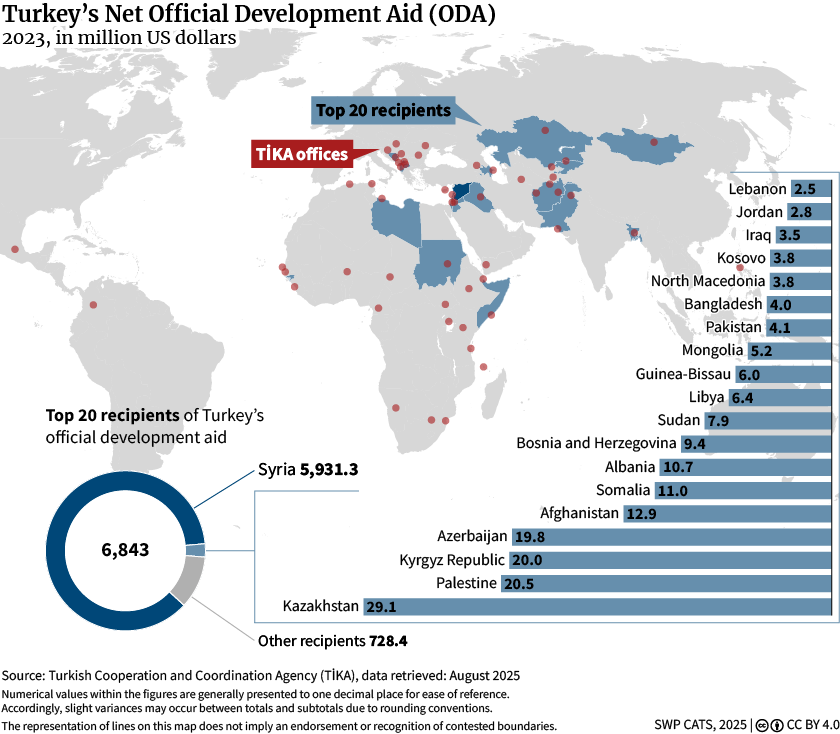

Although Turkey’s deployment of its military as a foreign policy tool has attracted considerable attention lately, there are other important dimensions of its foreign policy activism, such as its multilateral engagement with international organisations and the provision of large-scale development aid. As can be seen from the timeline provided in Figure 9, Turkey has sought to diversify its diplomacy in recent years, including through expressing interest in becoming a member of the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Figure 10 shows the overseas offices of the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) – the country’s main body for the provision of development aid – and the top recipient countries. And Figure 11 plots the evolution and scale of development aid over the past 15 years.

Source: TIKA Report, TIKA