© picture alliance / AA | Murat Kula

© picture alliance / AA | Murat Kula

Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, Salim Çevik, Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar

Supported by Maximiliane Schneider and Daniel Kettner

June 3rd, 2022

1. Introduction

2. Security and Defence Engagement

3. Diplomatic Activism

4. Economic Engagement in Africa

5. Turkey’s Soft Power Tools in Africa

As Turkey gradually expands its influence at the regional and global level, Africa has become a major area of focus for Ankara. Africa’s global significance is rising due to vast untapped resources, growing demographics, rapid urbanisation and the accompanying growth of the middle class. Thus, Africa is not only rich in terms of raw materials but it also represents an increasingly growing market. This led to the “new scramble for Africa” where all established and rising powers are vying for increased influence.

Turkish intention of reaching out to Africa was first declared by the then Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the publication of the Africa Action Plan in 1998. However, prior to 2005, which was declared the “Year of Africa”, Turkey’s relations with Africa was confined mostly to the states of North Africa, with whom Turkey shares a common history and religion. Today, Africa is one of the regions in which Turkey’s new foreign policy activism is most visible. Turkish-Africa relations are now institutionalised through the establishment of periodical Turkey-Africa summits. The growing importance given to Africa reflects the Turkish desire to diversify economic and military relations. It is also part of Turkey’s efforts to present itself as a regional and global actor. Expansion to Africa is one of the few topics that the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, AKP) government has consistently pursued, since coming to power in 2002. Moreover, since this policy is largely considered a success story, it will likely be appropriated by other political parties, if and when there is a change of government in Turkey.

This visual platform aims to provide an overview of Turkey’s increased foreign policy activism in Africa. It is mainly based on primary data sources. These sources are listed in detail underneath the visuals. Additionally, the parts on diplomatic activism, economy, and Turkey’s soft power tools draw upon the growing and highly valuable literature on Turkey’s engagement in Africa, such as Tepeciklioğlu (2020), García (2020), Donelli (2021), and Orakçi (2022).

Turkish policy in Africa is comprehensive and encompasses diplomatic channels, airline connectivity, economic cooperation, trade, investments, development and humanitarian aid, the provision of health services and education, cultural cooperation, as well as religious and civil society activism. Particularly, on the rhetorical level, Turkey distinguishes itself from traditional Western actors, especially former colonial powers by emphasizing cultural and humanitarian proximities and activities.

In recent years, Turkey has integrated a military and security component into its economic, political, and cultural relations with African states. And while Ankara’s increased military and security interaction with African states has raised serious concerns in the West, Turkey has only a limited capacity to project military power in distant regions. But Turkey seeks to expand its economic engagement and actively cultivate its diplomatic relations with the continent.

Overall, across the entire continent, Turkey has limited capabilities compared to more traditional powers such as the US, France, Great Britain, and the EU and rising powers such as China and Russia. However, it is creating pockets of influence where it challenges these actors and makes use of its cultural and diplomatic strength. Furthermore, Turkey itself is a rising actor. Its influence in economic, diplomatic and military realms is growing much more rapidly than that of traditional powers, leading to the projection that Turkey will become an even more important actor in Africa. The EU needs to recognise the growing footprint of Turkey and look for opportunities for cooperation rather than solely focusing on competition.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1998 | African Action Plan presented by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

| 2005 | Declared as the “Year of Africa” |

| 2005 | Turkey was granted observer status by the African Union (AU) |

| 2008 | Turkey became a strategic partner in the AU |

| 2008 | 1st Turkey-Africa summit, in Istanbul |

| 2011 | Turkey's emergence as primary actor in Somalia |

| 2014 | 2nd Turkey-Africa summit, in Malabo (Equatorial Guinea) |

| 2021 | 3rd Turkey-Africa summit, in Istanbul |

Sources: Own compilation

↑ To the Table of Contents

While Turkey strengthens its economic and political relations with African countries, it also aims to enhance its military cooperation and peacekeeping initiatives across the continent.

Security and defence cooperation with several African countries exists at different levels, including defence industry cooperation, defence cooperation, military training, and cooperation in combating terrorism and organized crime. Since the announcement of the Africa Action Plan in 1998, Turkey has signed security and defence-related agreements with 30 states in Africa. In addition, Turkey maintains military attachés in 19 African countries (see Figure 1).

Currently, Turkey maintains military bases in two African countries, Somalia and Libya, and provides military training in these countries in the context of partner capacity building. In 2017, Turkey established the Somali Turkish Task Force Command (Camp TURKSOM) in Mogadishu which is the largest Turkish military training centre abroad. Turkey has operated five training centres in Libya since 2020. In addition to military training, Turkey also provides the necessary equipment for the security apparatus of these states.

Besides its military capacity-building efforts, Turkey contributes to various UN peacekeeping operations in Africa.

Figure 1: Turkey’s Security and Defence Cooperation with African States

Sources: Official Gazette, Turkish Armed Forces, Anadolu Agency

| Mission Code | Country | Personnel Types (Group) | Sum of total | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNMISS | South Sudan | Individual Police | 26 | 2005* |

| MONUSCO | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Individual Police | 8 | 2006** |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Individual Police | 5 | 2019 |

| UNAMID*** | Darfur/West Sudan | Individual Police | 3 | 2006 |

| UNITAMS | Sudan | Individual Police | 1 | 2020 |

* First Turkish contribution to the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), the preceding mission to the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).

** First Turkish contribution to the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC), the preceding mission to the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).

*** The UN-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) completed its mandate on 31 December 2020. The United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) continues to support the transition in Sudan.

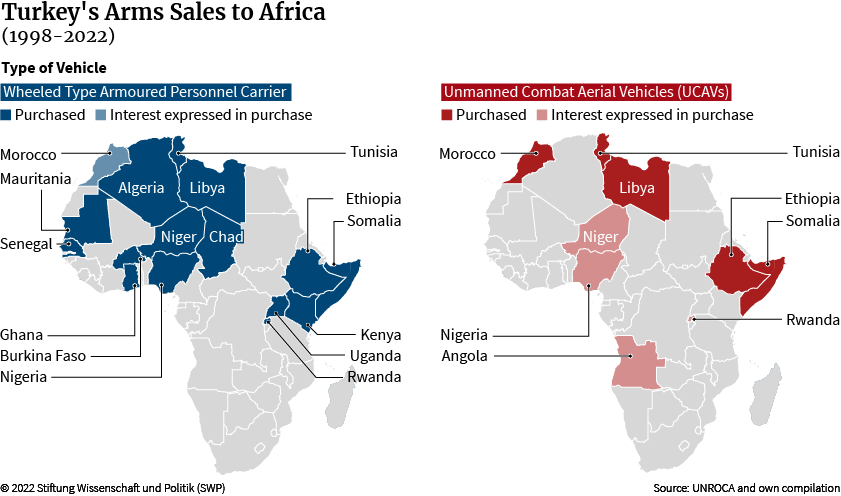

Figure 2: Turkey’s Arms Sales to Africa

Sources: United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) and own compilation

Since its engagement in Somalia in 2011, Turkey has been positioning itself as an important security actor in Africa while promoting its thriving defence companies. African countries have become increasingly interested in buying Turkish military equipment, especially its more affordable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) as well as armoured vehicles. Turkey's armoured vehicles expand its footprint in Africa as the UAVs are in high demand after their combat-tested success in various conflict theatres such as in Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkish defence companies initially entered the African market with small arms and later began to export tactical wheeled armoured vehicles. Today 15 African states operate with armoured vehicles, made by several competing Turkish firms. In recent years, a number of African states such as Kenya, Tunisia, Uganda, Chad, and Senegal have placed large orders and Turkish firms have secured their place in the African market. Turkish UAVs, most prominent the Bayraktar TB2 armed drones - produced by Baykar - are operational in Morocco, Somalia, Libya, and Ethiopia, while Tunisia has also begun to use Anka UAVs, manufactured by Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI).

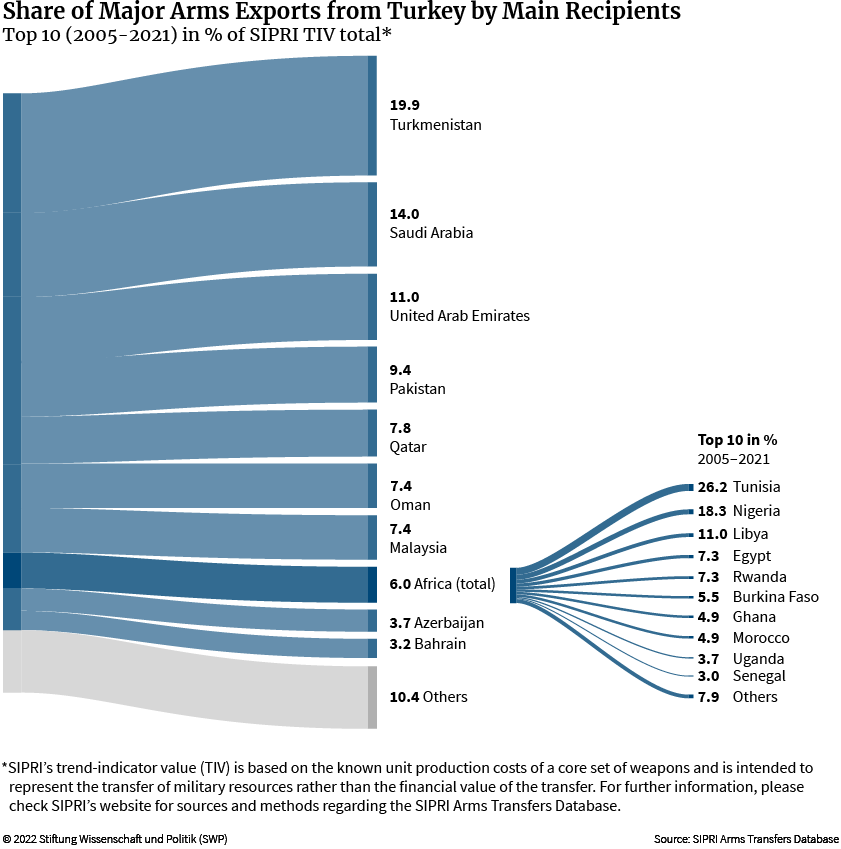

Figure 3: Share of Major Arms Exports from Turkey by Main Recipients

Sources: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Geographically, the main recipients of Turkish arms exports are concentrated in West, East and North African countries. The top 10 recipients of Turkish arms include Tunisia, Nigeria, Libya, Egypt, Rwanda, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Morocco, Uganda and Senegal. Meanwhile, the sales to Egypt, 4th in the ranking, were before the relations collapsed in 2013.

Figure 4: Turkey’s Defence and Aerospace Exports to Africa

Sources: Turkish Exporters Assembly (TIM)

According to the figures of the Turkish Exporters Assembly which also include civil aviation exports, Turkey’s arms sales reached a record high between 2015 and 2021 with the biggest increase in African countries. In the sectoral ranking of Turkey's export industries, the defence and aerospace industry jumped from 18th in 2020 up to 13th in 2021. The main defence industry products that Turkey sells to African countries include UAVs, armoured vehicles, electro-optical sensor systems, surveillance systems, mine clearance vehicles, and rifles.

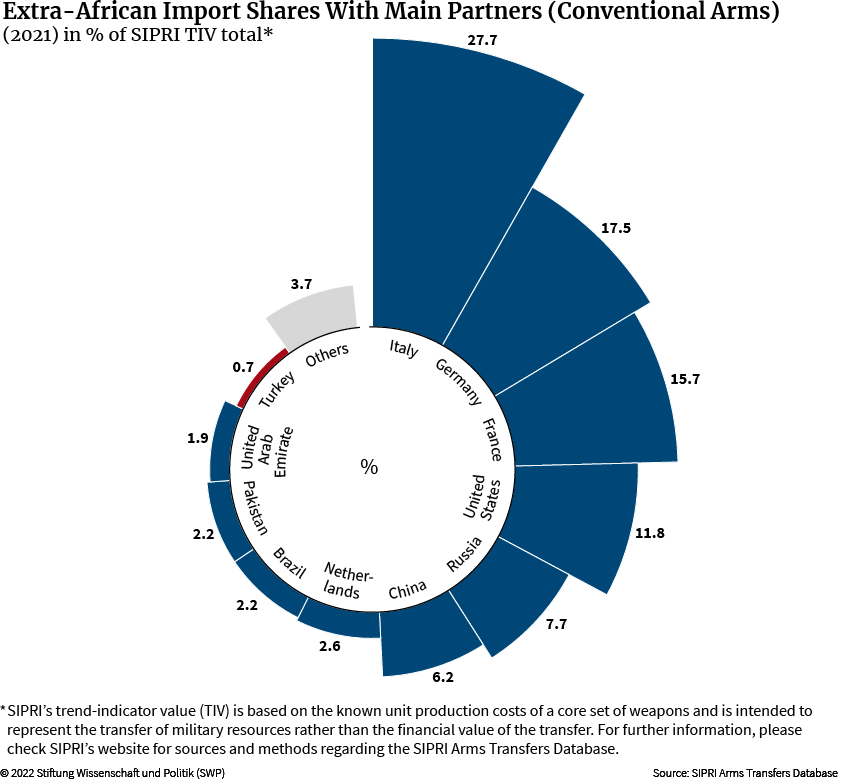

Figure 5: Extra-African Import Shares with Main Partners (Conventional Arms)

Sources: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Turkey is a rising player with the potential to offer competitive prices and solutions, with a no-strings-attached policy, for African countries. However, despite the skyrocketing sales in 2021, which created a substantial jump in the sectoral ranking, Turkey is still lagging behind the most influential countries in the regional market such as Italy, Germany, France, the US, Russia, and China according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

↑ To the Table of Contents

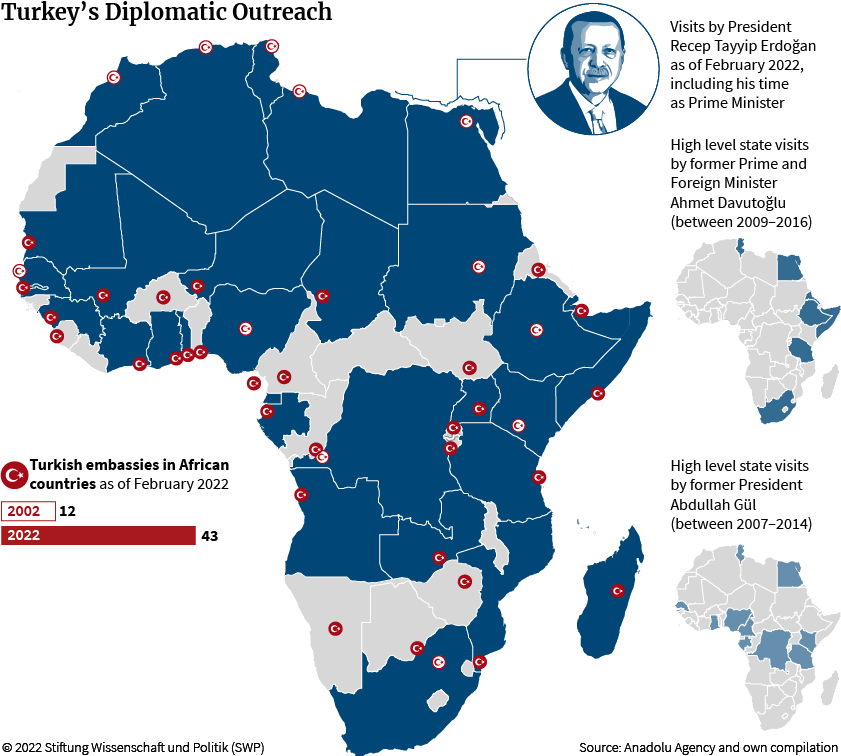

Figure 6: Turkey’s Diplomatic Outreach

Sources: Anadolu Agency and own compilation

The expansion of diplomatic missions throughout the continent and the increasing number of high-level state visits from Turkey to Africa is a reflection of Turkey’s diplomatic activism in Africa. Prior to 2002, Turkey had embassies only in 12 African countries. However, by 2022, this number increased to 43. Today, Turkey is the fourth most represented country in Africa after the United States, China, and France. Meanwhile, Turkey’s diplomatic outreach was reciprocated by the African countries as well, as the number of African embassies in Ankara rose from 10 in 2008 to 37 in 2021.

Turkey's president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan takes personal charge of the country’s Africa policy, backing it with intense travel diplomacy and strategic appearances. Throughout his tenures as prime minister and president, has thus far paid 52 state visits to 31 countries across the continent. Today, this makes Erdoğan the leader that has paid the highest number of visits to Africa from outside the continent. During his visits, he is often accompanied by business people and civil society representatives. These visits lay the groundwork for furthering economic relations, aid provision, cultural cooperation, and civil society activism and more recently, military cooperation.

↑ To the Table of Contents

One of the most important drivers of Turkey’s Africa policy is economic cooperation and trade. Over the last two decades, Africa has become home to many of the world’s fastest-growing economies, offering unique opportunities for trade and investment. Similar to global players such as China, the US, the EU, and India, Turkey also strives for greater access to Africa’s resources, markets, and strategic locations by offering financial investments in infrastructure and finished products. In this regard, Turkey's economic relations with Africa have witnessed a remarkable expansion.

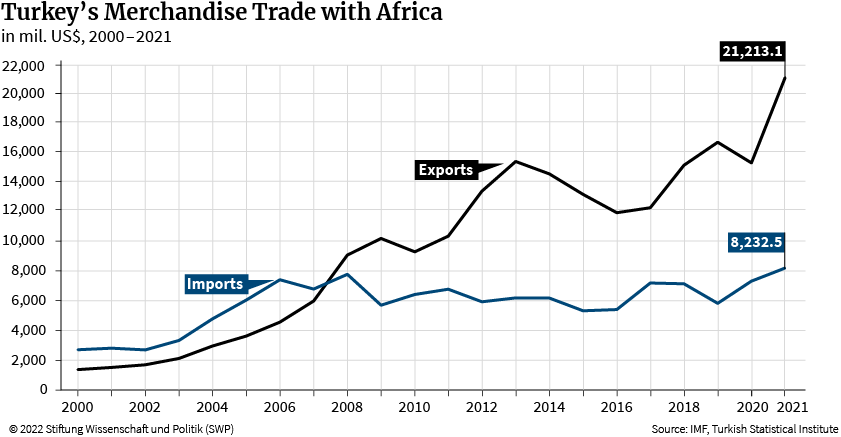

Since Turkey started its African Initiative Policy in 1998, its total trade volume with Africa increased more than seven-fold from US$ 4.09 billion in 2000 to US$ 29.45 billion in 2021. Meanwhile, Turkey’s imports increased from US$ 2.71 billion in 2000 to US$ 8.23 billion in 2021, while its exports increased from US$ 1.37 billion to US$ 21.21 billion (Figure 7). Turkey extensively imports oil and LNG from African suppliers, and the main trade sectors are steel and cement, machinery, and textiles. According to the Turkish Ministry of Commerce, Turkey conducted free trade agreements (FTA) with Egypt, Mauritius, Morocco, and Tunisia, and an FTA with Sudan is in the process of ratification. The FTAs eliminate customs duties and taxes on trade in goods and services between Turkey and its partners. In recent years, Turkey also expanded to the markets in sub-Saharan Africa.

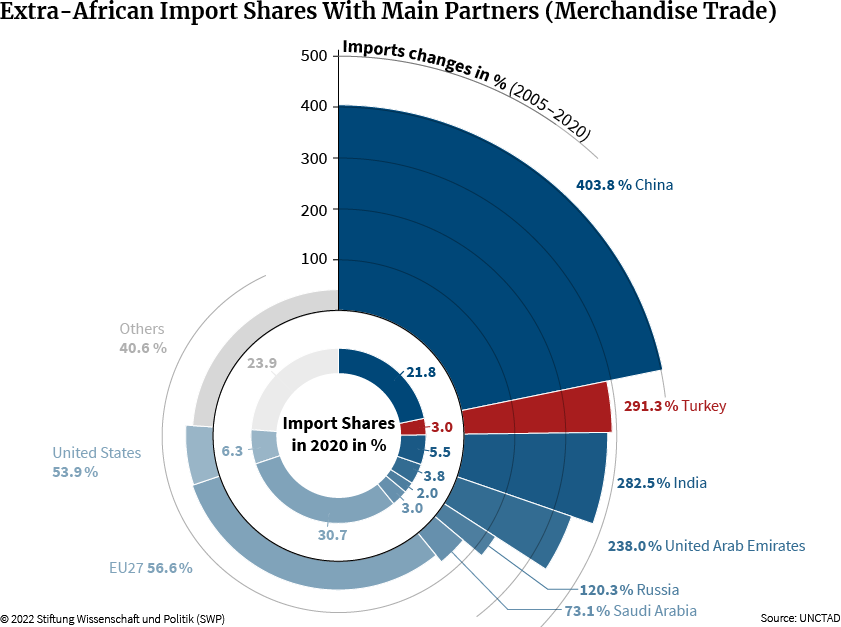

In the last decade, Turkey gained a growing trade surplus at the expense of Africa’s export market which might create a political problem in the long term. In fact, between 2005 and 2020, Turkey’s exports to Africa surged exponentially by 291 percent (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Turkey’s Merchandise Trade with Africa

Figure 8: Extra-African Import Shares with Main Partners (Merchandise Trade)

Sources: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

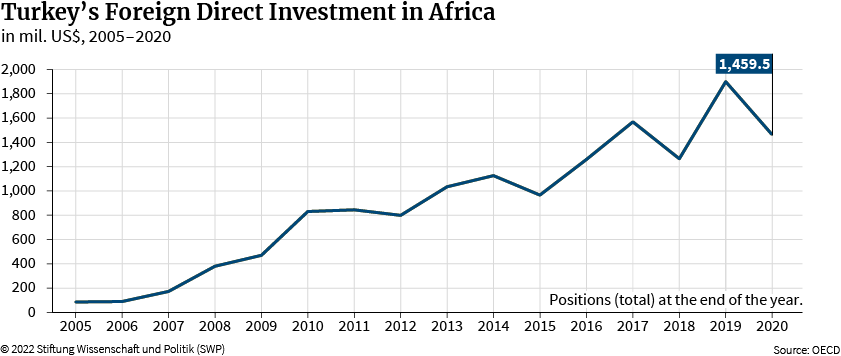

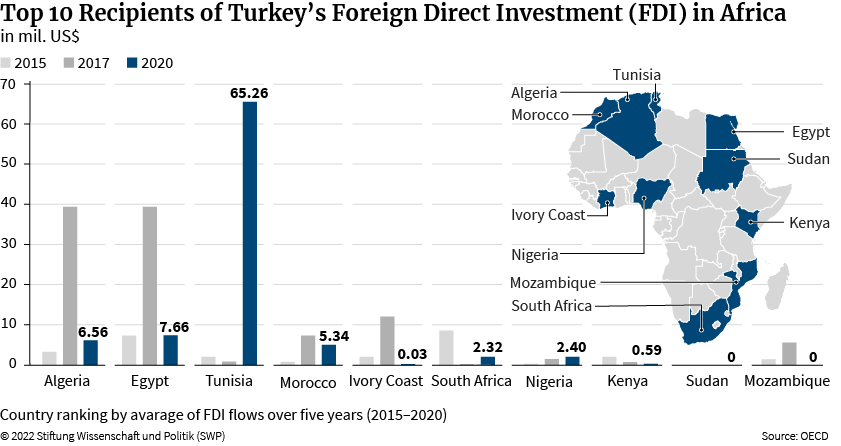

Since 2016, Turkey periodically organises Turkey-Africa economic and business forums in partnership with the African Union in order to regulate and develop trade relations between Turkey and the continent. Between 2005 and 2020, Turkey’s foreign direct investment (FDI) increased steadily, and is now close to US$ 1.45 billion (Figure 9). Turkey has mainly been investing in infrastructure development, construction and energy sectors in North Africa and recently began to expand towards West Africa and the Horn of Africa (Figure 10).

Figure 9: Turkey’s Foreign Direct Investment in Africa

Sources: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

While Turkey increases its investments steadily on the whole continent, the great amount of the overall investment is in northern African countries, namely in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Top 10 Recipients of Turkey’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Africa

Sources: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

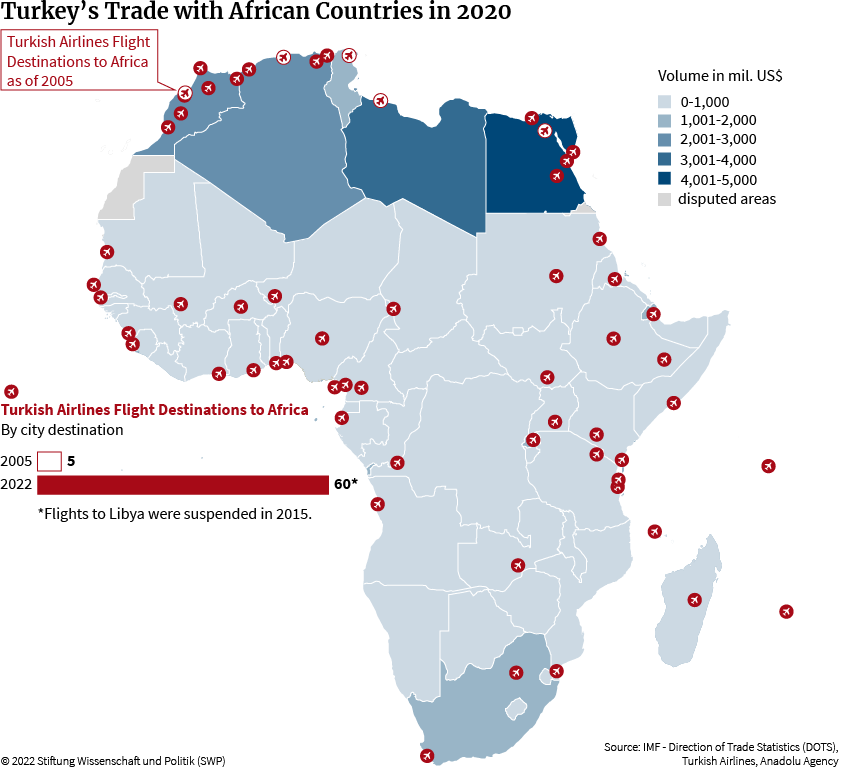

Turkey’s Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEIK) runs 45 business councils in African countries in order to promote bilateral trade and mutual investment. Turkish private companies are also monitoring Africa for investment and business opportunities. For example, Turkish Airlines (THY) flies to 60 different destinations in 40 African countries across the continent, whereas it only had five African flight destinations in 2005 (Figure 11).

The number of African countries with which Turkey signed Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreements reached 45 in 2017, while it was 23 in 2003. Turkey’s highest volume of trade is still with its traditional partners in North Africa rather than the broader continent. In spite of Turkey’s expanding economic presence in Africa, it is still weak in comparison to Africa’s more established partners such as the EU, China, the US and India who make large investments and have larger trade volumes than Turkey with the continent.

Figure 11: Turkey’s Trade with African Countries in 2020

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF) - Directions of Trade Statistics (DOTS), Turkish Airlines flight destinations (2005 and 2022 flight destinations), Anadolu Agency

↑ To the Table of Contents

Soft power tools had been at the core of Turkey’s Africa expansion. These tools include economic and humanitarian aid, the provision of health and education services as well as references to historical and religious identities. Turkish aid is particularly welcomed by the African countries as it comes with no political or economic conditionalities. While underlining this, Turkey distinguishes itself from other major powers. Turkey claims that its policies in Africa are solely humanitarian focused and designed for mutual benefit whereas other big powers, be it Western or non-Western, come to the continent with an exploitative mentality. In this direction, in sub-Saharan Africa, Turkey underlines its lack of a colonial past and in Northern Africa it points to common religious and historical ties.

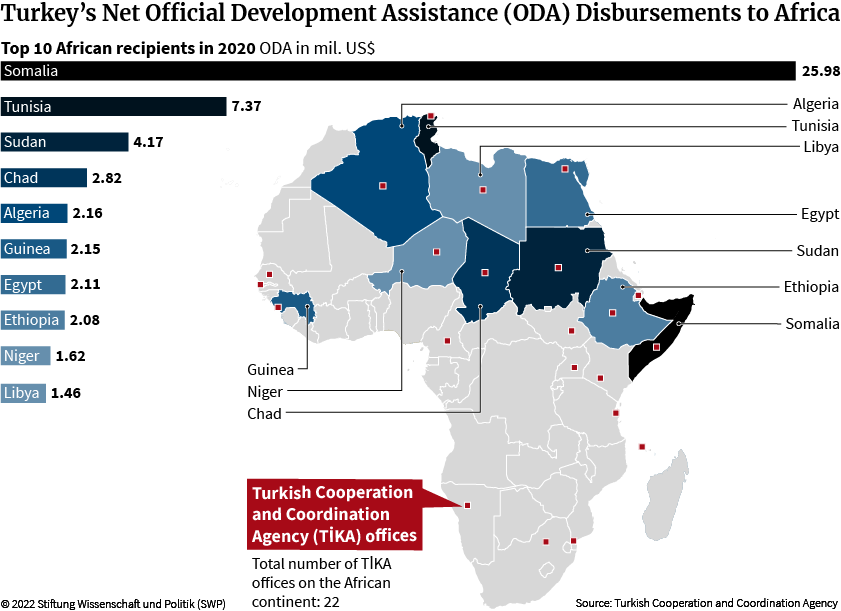

The political impact of Turkish aid provision is most visible in Somalia where Ankara in 2011, in the aftermath of a deadly famine, emerged as a key donor. Ever since then, Somalia had been the top recipient of Turkish Official Development Aids (ODA) in Africa (see Figure 12). Indeed, Turkish aid to Somalia over the last decade totals up to US$ 1 billion, making Turkey the top donor in the crisis-ridden country. This level of aid in a devastated region made Turkey not only a top donor but a political and military ally for the Mogadishu government.

Figure 12: Turkey’s Net Official Development Assistance (ODA) Disbursements to Africa

Sources: Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA) offices and figures

Overall, development aid has been an important dimension of Turkish foreign policy in Africa. Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA) – Turkey’s main agency for the provision of development aid – runs 22 offices in Africa and has so far conducted more than 7000 development projects (see Figure 12).

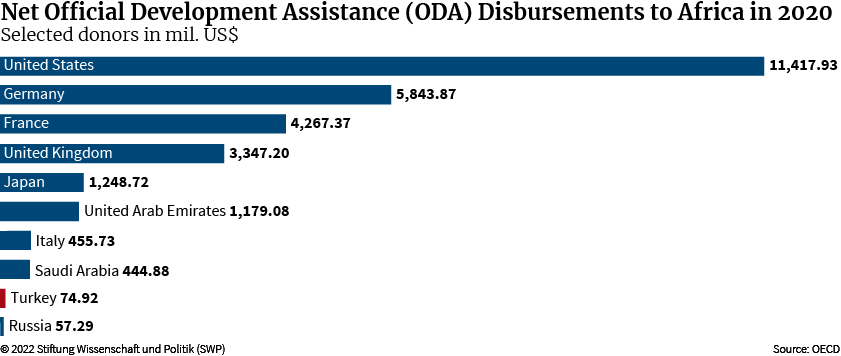

Figure 13: Net Official Development Assistance (ODA) Disbursements to Africa in 2020

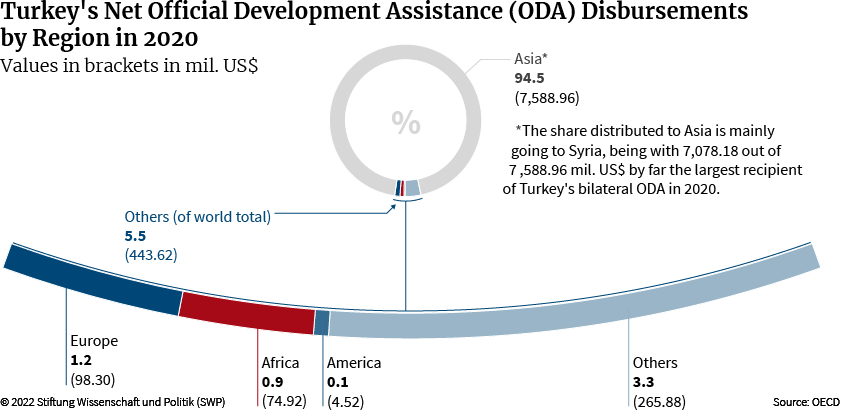

Figure 14: Turkey’s Net Official Development Assistance (ODA) Disbursements by Region in 2020

Sources: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

At the global level, Turkey is one of the top donors of development aid. However, a huge chunk of Turkish development and humanitarian aid goes to Syria. As Figure 14 demonstrates, Africa as a continent received only 0.9 percent of Turkish ODA in 2020. When compared to other top donors in Africa, this puts Turkey way behind in the list of top donors (Figure 13).

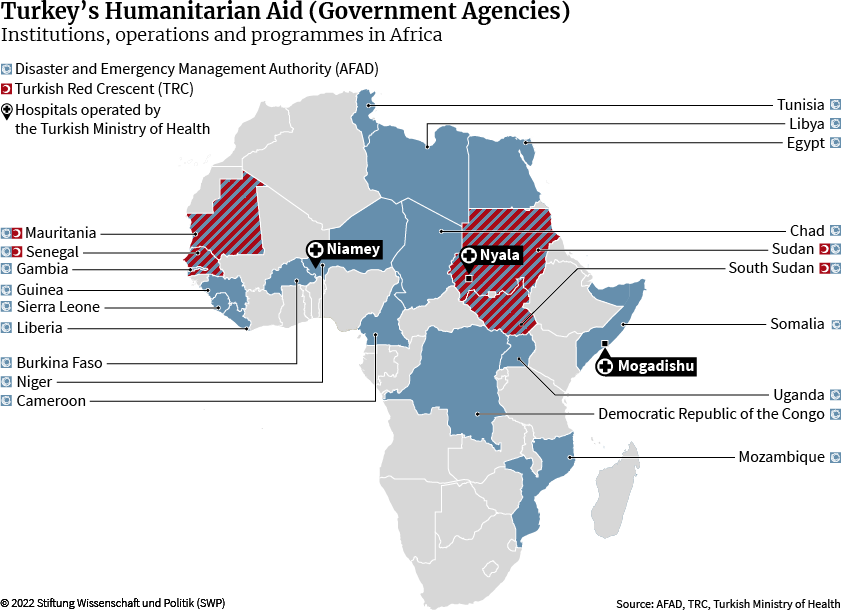

Figure 15: Turkey’s Humanitarian Aid (Government Agencies)

Sources: Turkish Red Crescent (TRC), Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), Turkish Ministry of Health (hospitals in Somalia, Sudan and Niger)

Turkey tries to compensate its numerical weakness in the provision of ODA, by focusing on humanitarian aid, particularly in the health sector and disaster management. Through the activities of its Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) and the Turkish Red Crescent, Turkey had created a wide array of humanitarian aid services throughout the continent. Turkey also operates three hospitals across Africa. The presence of Turkish doctors and aid workers directly on the ground distinguish Turkey from other external actors and enables Turkey to make very effective use of its limited resources to generate soft power.

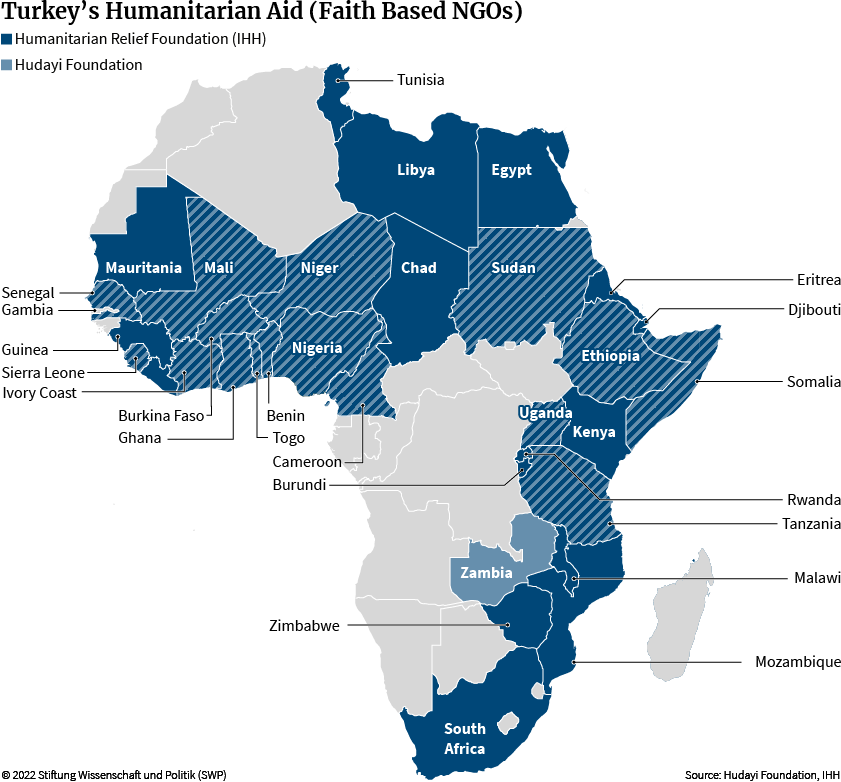

Figure 16: Turkey’s Humanitarian Aid (Faith Based NGOs)

Sources: Humanitarian Relief Foundation, Hudayi Foundation (source 1, source 2)

A significant aspect of Turkish ODA is the importance of non-official organisations (civil society organisations) in the provision of humanitarian aid. These are almost entirely religious organisations, doing various types of charity such as drilling water wells, funding schools, madrasas (religious educational institution) and orphanages, food distribution, particularly the distribution of the meat of sacrificed animals during the holy week of Eid al Adha (festival of sacrifices), free healthcare, and surgery conducted by volunteer doctors from Turkey. These activities are hard to quantify and visualize as they are conducted by a plethora of organisations in a quite decentralized and ad hoc manner. The Figure 16 presents only the activities of the IHH and the Hudayi Foundation, which are the largest and most centrally organised entities active in Africa. These organisations along with several smaller ones have been immensely helpful in branding Turkey as an aid provider and strengthening its soft power. Moreover, since these are grassroots activities based on volunteers, they provide important and durable human-to-human contact between Turkey and Africa. The dimension of religiously motivated volunteering suggest that these activities will probably be more sustainable and will not be affected by domestic political changes in Turkey. In fact, activities of certain NGOs in the continent predate the interest of Turkey as a state that sees Africa as a new region of influence and will likely remain robust even if there is a change of government in Ankara.

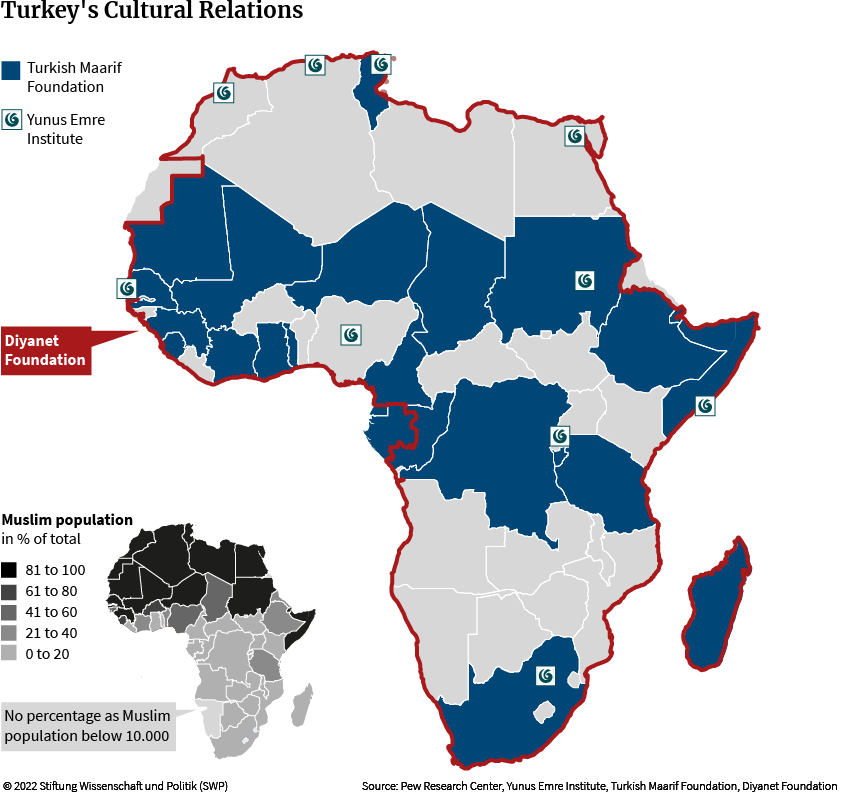

Figure 17: Turkey’s Cultural Relations

Sources: Diyanet Foundation, Pew Research Center, Turkish Maarif Foundation, Yunus Emre Institute (source 1, source 2)

Turkey also has a series of government agencies which instrumentalize culture and identity, and in particular common religion as assets in its soft power projection. The Yunus Emre Institute, which promotes Turkish language and culture globally, runs 10 centres in Africa. Aside from South Africa and Rwanda, these centres are all located in Muslim majority countries. Diyanet, Turkey’s official institution responsible for managing religious affairs is active almost across the entire continent. Diyanet also conducts humanitarian aid, as well as building mosques, and providing religious education and scholarships to students to study in Turkey.

Education is a major component of Turkish soft power investment in Africa. Since the 1990s, the Gülen movement, an Islamic organisation with a transnational network of educational and social institutions, has set up several schools in Africa. Initially these schools were at the cornerstone of Turkey’s cultural diplomacy in the continent. However, the Gülen movement and the AKP fell in conflict with each other in 2013, prompting Turkey to establish the semi-public Maarif Foundation in 2016 to globally counter, and if possible replace, the education network of the Gülen movement. Today, the Maarif Foundation runs 191 schools in 25 countries in Africa. Several official and non-official organisations provide scholarships to African students to study in Turkey. The major organisation to provide scholarships is the Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB). Between 2012 and 2021, 12,600 students from 54 African countries were provided with grants from the scholarship programme of YTB. The number of YTB scholarships presents an upward trend particularly since 2016. Combined with other scholarship programmes and students who come to Turkey at their own expense, the total number of African students in Turkish universities reached 36,851 by the 2020-2021 academic year.

↑ To the Table of Contents